JetZero and Natilus Pitch BWB Alternatives to Airbus, Boeing Narrowbodies

JetZero, a start-up company based in Long Beach, California, is developing a blended-wing-body (BWB) aircraft for the so-called “middle of the market” (MOM) segment occupied by the remaining Boeing 767-300ER and 757 models, older and current-generation Airbus A321s, and the forthcoming Boeing 737-10. Older Airbus A330 variants and current-generation aircraft such as the Boeing 787, Airbus A330neo, and A350-900 also serve this segment.

The design is a 250-passenger airliner, the same size as the larger “new midsize airplane” (NMA) concepts that Boeing explored but did not bring to fruition. JetZero says the BWB will be 30% more aerodynamically efficient than the aircraft it replaces. The company compares the economics of its Z4 aircraft with the Boeing 767-200ER. It has not compared the Z4 with the current-generation aircraft that the BWB would actually compete against for sales and costs.

Michel Merluzeau, head of sales engineering and market development for JetZero, said the MOM has an “addressable market” of 12,000 aircraft. However, he said this does not reflect the anticipated share that might be captured by the Z4, a figure he did not disclose. Merluzeau was speaking at the annual Pacific Northwest Aerospace Alliance conference on Wednesday in Lynnwood, Washington.

Engine challenges

An analysis by LNA indicates that the problem for JetZero is that the wing’s large size requires it to fly above 41,000 feet to reduce parasitic drag, which is the maximum altitude of an A321neo or 737 Max. At such high altitudes, high-bypass turbofan engines such as the CFM LEAP and Pratt & Whitney geared turbofan (GTF), which power the 737 Max and A320neo, experience thrust loss. The 40,000-plus-foot regime is typically occupied by super-long-range business jets powered by low-bypass engines.

Unfortunately, the LEAP and GTF engines are too small for JetZero’s project. So, the company has opted for three-generation-old Pratt & Whitney PW2040 engines to power its first full-scale demonstrator instead. JetZero has not yet committed to an engine for its subsequent production model.

The PW2040, a lower-bypass engine similar to those used on business jets, meets JetZero’s altitude thrust-decline requirements; however, its fuel consumption is not comparable with that of modern engines such as the LEAP or GTF. JetZero and Pratt & Whitney claim this can be improved. However, typically, even major updates to existing engines yield improvements of less than 5%.

Compared with today’s GE9X, the most modern engine in flight test, the PW2040 would deliver 25% higher fuel consumption, so the project is dangerously close to delivering only marginal improvement on a new, unproven technological airframe without showing a significant operational fuel cost gain at this stage.

In January, JetZero announced that its latest Series B funding round raised $175 million, bringing the company’s total funding to over $1 billion. JetZero said the funds will support the development of the full-scale technology demonstrator, which the company aims to start flight testing in 2027. It has selected a site in Greensboro, North Carolina, for Z4 manufacturing and final assembly and plans to break ground on the facility this year.

Natilus raises $28 million

Another company pursuing a BWB concept is Natilus of San Diego, California. It announced on Tuesday that it raised $28 million from private sources. This fledgling company has now raised $33 million, a fraction of the $250 million it says it needs to bring its first BWB model, the Kona freighter, to market. A 200-passenger BWB, the Horizon Evo, will follow.

That fresh capital “puts [Natilus] in a very comfortable position to really meet two major milestones,” Natilus co-founder and CEO Aleksey Matyushev told AIN. “The first one is really to get to full-scale first flight,” which the company aims to achieve with its Kona demonstrator in about 24 months. The second milestone will be the completion of wind tunnel testing for the Horizon Evo program.

“We already have a lot of the technology, I would say, ‘buttoned up,’ but there's still a lot of work to be done,” Matyushev said of the Horizon Evo. “We're hoping to be in the wind tunnel…sometime this year to validate a lot of our computational tools and to make sure that we're on the right track.”

The Kona is a small BWB powered by Pratt & Whitney Canada turboprop engines. For the larger Horizon Evo concept, Natilus intends to use Pratt & Whitney GTF or CFM LEAP engines. Kona is designed to have 50% lower operating costs and burn 30% less fuel than similar freighters. Its payload is 3.8 metric tons with a range of 900 nm.

Kona

Matyushev said the smaller, turboprop-powered Kona freighter will lay the foundation for the larger passenger-carrying Horizon Evo. This remotely piloted airplane will compete with the Cessna SkyCourier and Caravan, ATR-72F, and the de Havilland Canada Otter.

How much will Natilus need to bring the Kona to service? The amount Matyushev says is surprisingly small.

“We believe $250 million from pencil through certification is what it will take to bring it to market,” Matyushev said. “I’ve led a lot of Part 23 programs in the business jet world and turboprop world… If they’re billions of dollars, then Cessna and Cirrus would be out of business.”

The timeline for entry into service (EIS) is short. “Kona’s first flight will be in 24 months, so that’ll be 2028. Market entry will be in 2029,” Matyushev says.

Natilus doesn’t have a production plant yet. The company expects to announce its site selection by the end of this year. However, it has a plant in San Diego to produce the first Kona. It’s about 250,000 sq ft. When the Horizon Evo is developed, Natilus plans a 3.5 million sq ft production plant. For comparison, Boeing’s 787 plant expansion at Charleston is 1.5 million sq ft, about the same size as its current plant. Boeing’s Everett factory is 4.3 million sq ft.

At full production, Natilus projects building 350 Horizon Evos per year, or 29 per month. Airbus is currently building 50 A320 family members at four sites, with plans to increase production to 75 per month. Boeing’s Renton factory had the capacity to build 63 737s a month on three lines before the Max crisis began in 2019. Under its recovery plan, Renton will be capped at 47 aircraft per month. Boeing has not announced the production capacity of its new “North Line” in Everett, Washington, but the single line may be able to produce 15 737s a month.

Horizon Evo

Natilus’ mainline BWB, the Horizon Evo, will compete with the Airbus A320neo and Boeing 737 Max families. Natilus claims the Horizon Evo will have 40% more capacity than equivalent Airbus and Boeing aircraft, 50% lower operating costs, and 25% lower fuel burn.

Unlike Jet Zero, which compares its Z4 to the long-out-of-production 767-200ER, Natilus compares the Horizon Evo to today’s neo and Max. The Horizon Evo will have a range of 3,500 nm, which is far less than the 4,700 nm Airbus advertises for the A321XLR. Airbus advertises a range of 3,400 nm for the A320neo. The proposed Airbus A220-500, with up to 180 passengers in high density, is expected to have a range of around 2,800 nm to 2,900 nm. Boeing’s 737 Max 8 (737-8), Max 9 (737-9), and Max 10 (737-10) have advertised ranges of 3,500 nm, 3,300 nm, and 3,100 nm, respectively.

The Horizon Evo differs from JetZero’s in a number of ways. JetZero’s Z4 BWB is for the 250- to 300-passenger midmarket segment. The Horizon Evo concept competes with the A320 and 737 in the 120- to 180-seat sector that has far more market potential than the MOM sector. It’s also a size that doesn’t lend itself to a BWB design, according to Airbus. A BWB is better suited the larger it is, Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury said last year.

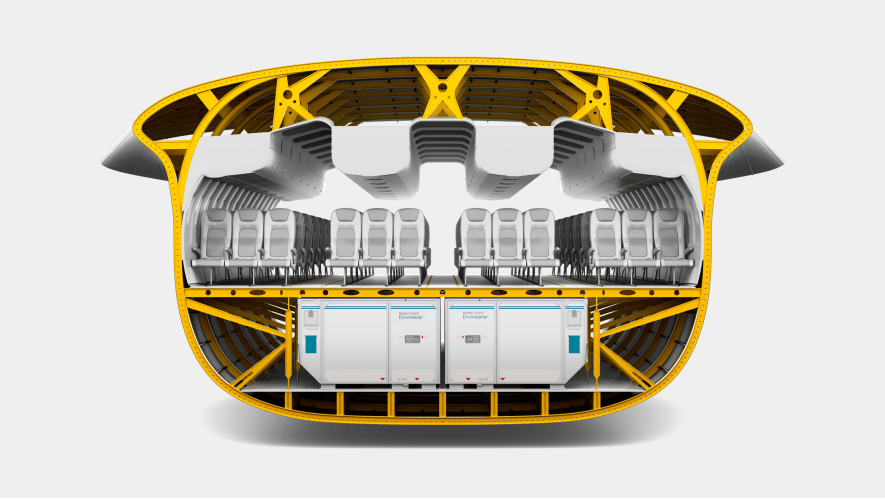

Regardless, Horizon Evo is also a dual-deck design, unlike the Z4. JetZero’s concept doesn’t allow meaningful cargo space below the passenger deck; Horizon Evo can take LD3 containers.

Natilus announced the switch from a single-deck to a dual-deck design for the Horizon Evo on February 10. Matyushev told AIN that the design change was largely driven by gate operations, referring to the 118-foot wingspan limit at gates accommodating most Boeing 737 and Airbus A320-family aircraft.

“If you make it a single-deck configuration, like other players in the marketplace, what you see is a very wide fuselage and a very small, stubby wing, so it looks very weird, and aerodynamically, it just doesn't fly very well,” he said. “For us, moving into a dual-deck configuration with a dedicated upper [passenger deck] and lower-deck cargo, we're able to shrink or tighten that fuselage up.” The updated configuration also enables faster passenger egress times with more door access, he explained.

While the JetZero Z4 has few passenger windows, Natilus’ Horizon Evo design now includes a window line for passengers, thanks to its high-wing design, versus JetZero’s traditional low-wing concept.

Horizon’s planned use of the GTF or LEAP engine with a higher bypass ratio contrasts with the Z4’s planned use of the 1970s-technology Pratt & Whitney PW2040, used on the Boeing 757 and the military Boeing C-17 cargo transport. The lower-bypass PW2040 is better suited for cruising at 41,000 feet, says JetZero.

Matyushev says the GTF and LEAP work on the smaller Horizon, which is designed to cruise at 35,000 feet.

While Matyushev says the Kona needs $250 million for development, certification, and EIS, LNA estimates that upwards of $900 million is a closer figure. Matyushev says the Horizon needs $3 billion to $5 billion, a figure LNA estimates is significantly underestimated. JetZero says it needs $7 billion to $10 billion for the Z4. LNA also believes this number is way too low.

Natilus has not disclosed many customers or the total amount of capital it has raised so far, but it claims to have a backlog of orders for 580 aircraft with a potential value of up to $23 billion. Canadian cargo airline Nolinor previously announced a firm order for an unspecified number of Kona aircraft, and Dallas-based Part 135 operator Ameriflight has signed a preliminary sales agreement covering up to 20 Kona freighters.

In December, Natilus announced a partnership with Indian low-cost carrier SpiceJet, which has signed a conditional purchase agreement for up to 100 Horizon Evo aircraft. To support operations in India, Natilus established a Mumbai-based subsidiary called Natilus India. Matyushev said the company is exploring other opportunities on the Asian continent, particularly in Southeast Asia, where “markets are very hungry for new development, new ideas, as well as airplanes in general.”